How Does Your Garden Grow?

Spring is in the air and so is the pollen! As we shake off the last frosty days of winter, many plants are blooming and turning Thomasville into a beautiful sight to behold. And many people are getting out and returning to their gardens. With several historic garden clubs in our area and a rose show that has been around for over a century, it’s no wonder that the flora of Thomasville is uniquely lush and beautiful.

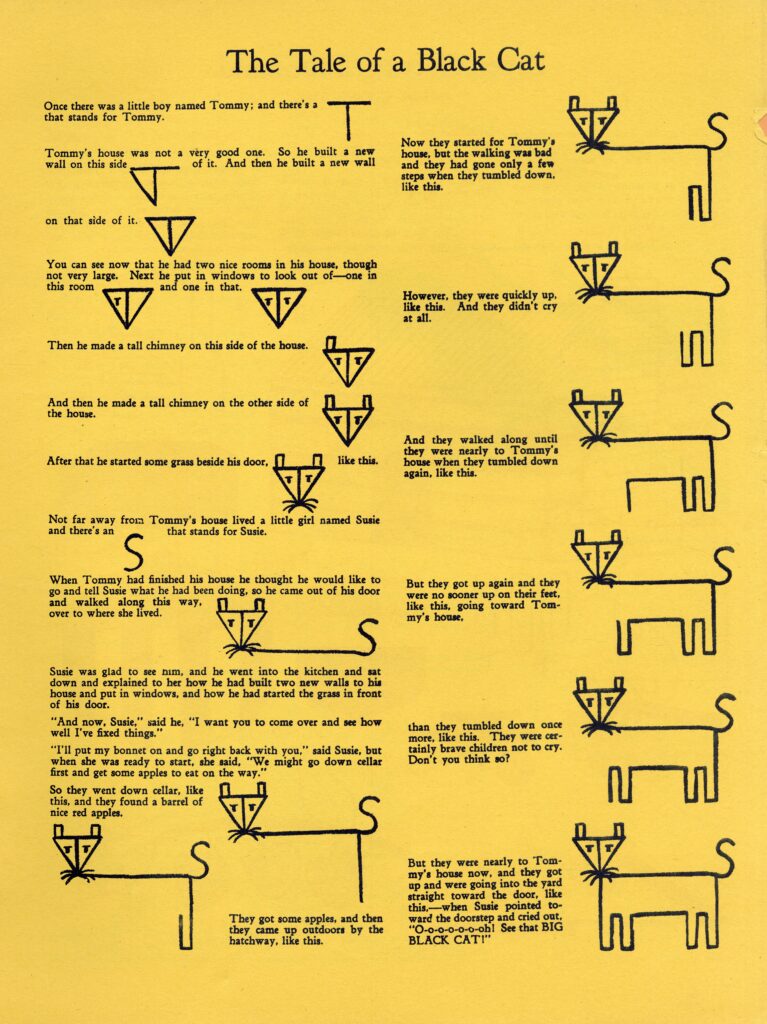

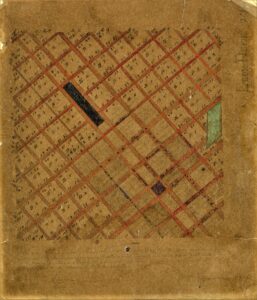

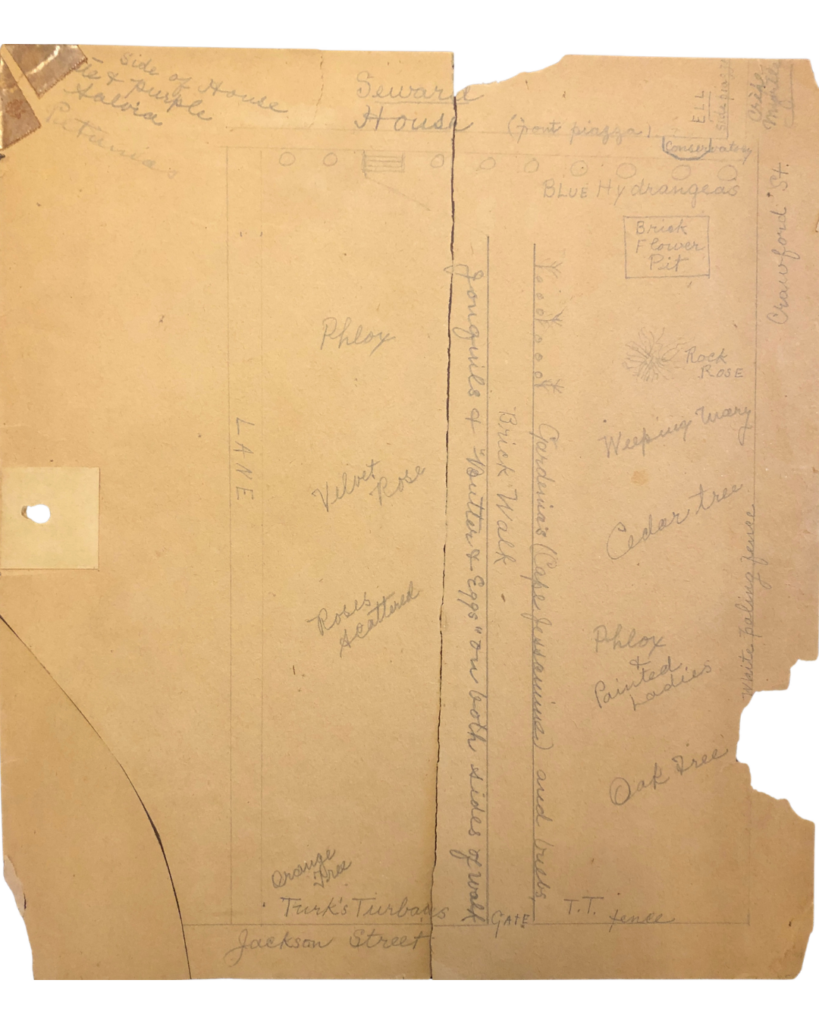

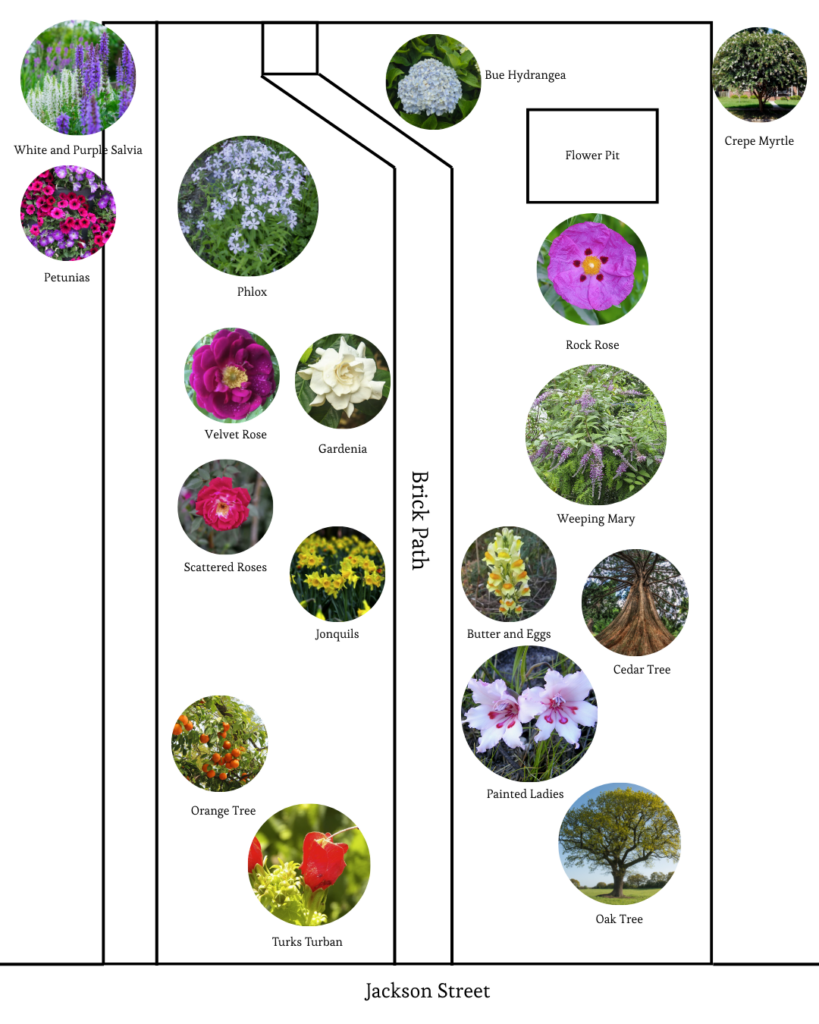

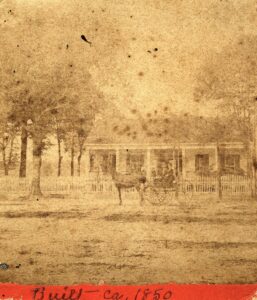

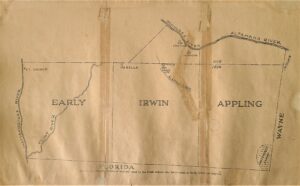

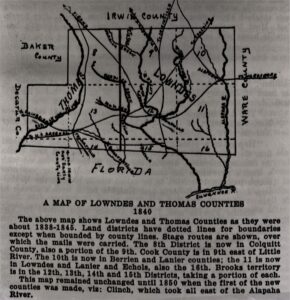

If you’re looking for ideas for transforming your garden, why not take a historic approach? The History Center’s collections offer us many pictures of past gardens, but a deeper look through the files shows us a map of a very special garden – the original 19th century garden that once decorated the front yard of the Seward House. This layout can be easily recreated or worked on to create a classic Southern garden for any level of gardener (including those of us with sickly green and brown thumbs).

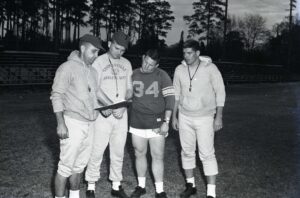

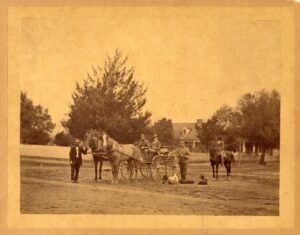

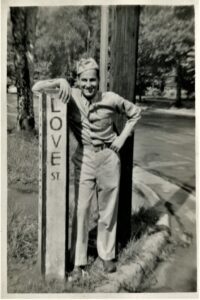

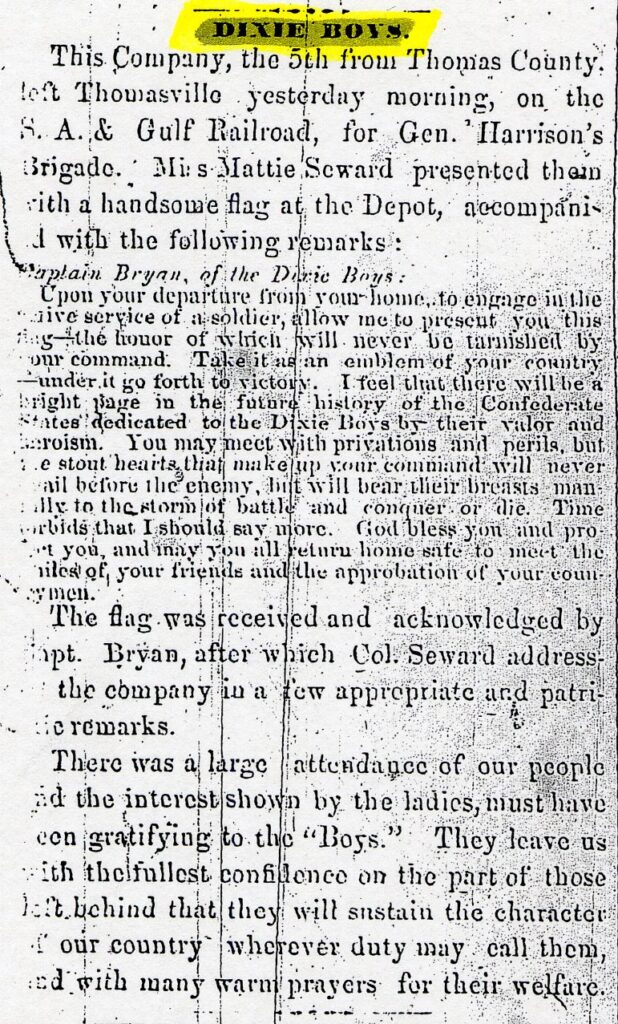

Before diving into the gardens, let’s get a little background on this house and why we have the garden plans in our collections. The Sewards in question for this property were Senator James Lindsey Seward (1813-1886) and his wife Frances Amanda Tooke Seward (1822-1897). Formerly located along the middle of Crawford Street facing Jackson Street, the site is now the location of several businesses including Hong Yip, the headquarters of the Republican Party in Thomasville, and AJ Moonspin. The house was likely built prior to 1865 and added onto with the gardens developing over that time.

Most of the plantings in this garden are familiar names to us: cedar, oak, hydrangeas, etc. But a few of them require a little deep dive to find the intended plant. For example, take the Weeping Mary (be sure to add “plant” after the name in your google search or else you’ll be flooded with religious iconography). The scientific name for this plant is Buddleja lindleyana. It is native to China but was introduced to the United States in the 1800s. The plant is reminiscent of wisteria in its growth habit (though a little less likely to take over your yard).

If you’re looking to add Phlox to your garden, there are several native varieties to pick from that are likely what the Sewards planted. Phlox subulata or Moss Pink and Phlox nivalis or Trailing Phlox are good for sunny areas. Have a shady spot? Try Phlox divaricate or Woodland Phlox or Phlox Pilosa (Downy Phlox) for those areas.

In the great Thomasville debate between camellias and roses, the Sewards seem to have been rose fans. One of the notes mentions “roses scattered” through the garden. These would have been what we now call antique varieties that existed before the first hybrids came about in the mid-late 1800s. Some cultivars include “Blush Noisette” which arrived in America in 1817, “Madame Plantier” in 1835, “Souvenir de la Malmaison” in 1843, and a Thomasville favorite, “Louis Phillippe” in 1834. The “Velvet Rose” mentioned likely refers to Rosa gallica or “Tuscany.” Thomas Jefferson received one of these in 1808.

But some of their roses aren’t roses. Rock rose or Pavonia lasiopetala is a Mediterranean plant that appears rose-like. Though not native to this country, this plant does well in rougher terrains. They’re even known to be fire-resistant!

Mixed between the jonquils and gardenias (or Cape jessamine as it is referred to here) is another flowering plant called “Butter and Eggs” or Linaria vulgaris. Like it’s name suggests, it is a light yellow and white colored flower that would have mixed in well with the yellow jonquils and cream gardenias.

Our Painted Ladies are Gladiolus carneus. This plant does not flower in the summer but in the winter, adding some beauty while the other plants lie dormant. It is native to South Africa and holds up well when cut for arrangements.

Along the fence line, the Sewards planted Turks Turbans. This could refer to several types of plants including a type of squash that produces brilliant red flowers and the cutest hat-shaped gourds. But in this case, the name likely refers to Mavaviscus arboreus from the hibiscus family.

Finally, if you want to recreate the garden faithfully, the map makes note of a “brick flower pit” close to the front of the house. This is your chance to be creative with your flower choice! This space would be great for wildflowers, experimental plants, or even an ornamental vegetable.

While this garden is long gone, there are many throughout Thomasville that still harken back to these historic plans. You may have some of these growing in your own yard or have seen them in your neighborhood as they start to bloom. But what do you think? How would your garden grow?

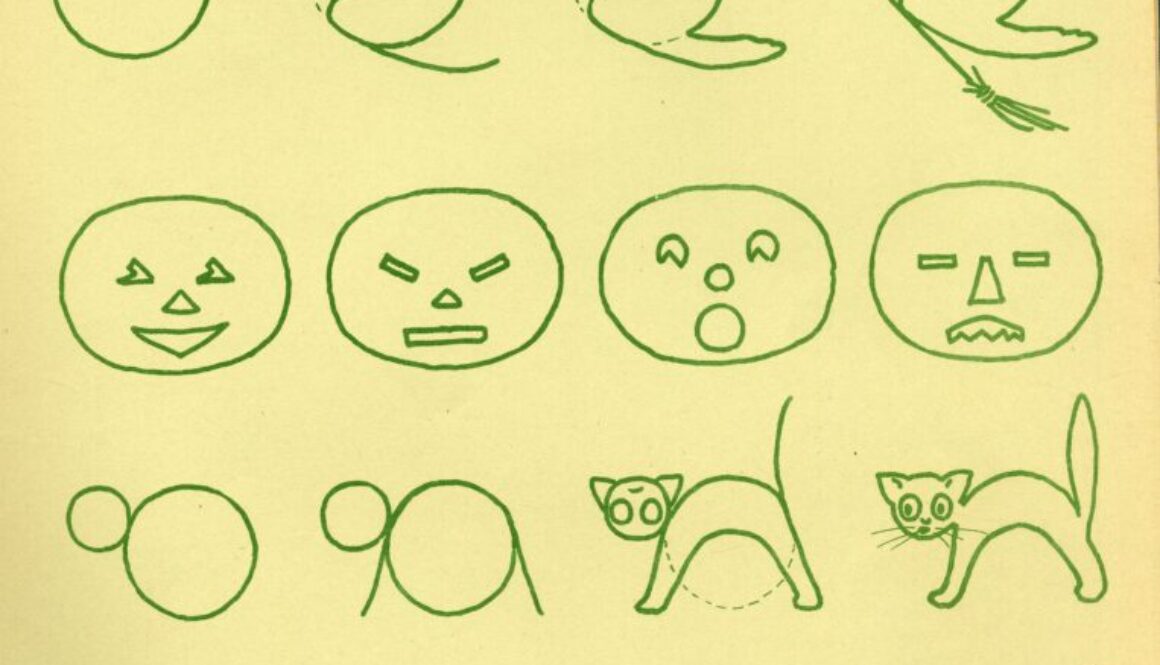

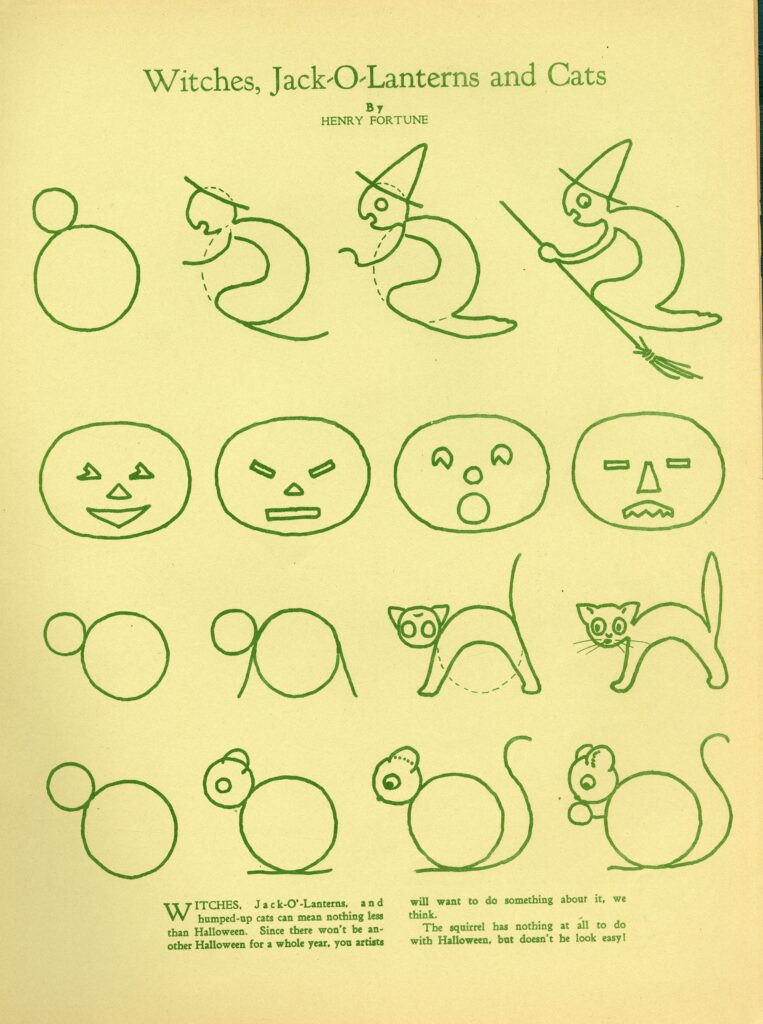

Our first lesson is in drawing. Using simple shapes like circles, you can add in detail to create something new from a spooky Jack-O-Lantern to a flying witch. What creepy Halloween critters can you come up with?

Our first lesson is in drawing. Using simple shapes like circles, you can add in detail to create something new from a spooky Jack-O-Lantern to a flying witch. What creepy Halloween critters can you come up with?