Community Patchwork Project

The process of using different materials to make a patchwork can be traced all the way back to ancient Egypt and China, where quilted funeral cloths have been discovered in tombs. Throughout time, patchwork has turned the practice of extending the life of fabrics into an art form that often tells a story about the culture of its artists. These patchwork quilts are treasured in communities all over the world, including our own in the Deep South: heirloom patchwork quilts can be found at the foot of our beds and on the walls of our homes.

The patchwork quilt has become a relic that tells a rich story: it can express emotion, provide warmth and comfort, and symbolize the life of a specific group of people. It is quite literally combining the fiber of our surroundings to make art that is deeply personal and culturally relevant.

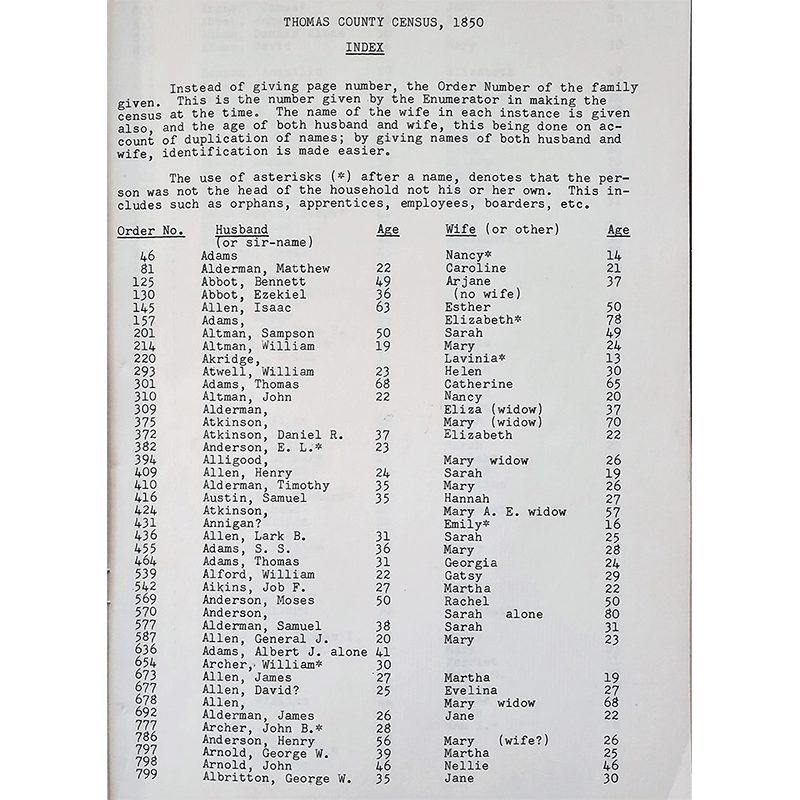

This patchwork project is an expression of our community and its people – like the patchwork quilt with a multitude of tones, colors, textures and shapes, this project tells a story of Thomasville and the people who live here: a patchwork of what we feel, what we envision, and what is most important to us here in our corner of Southwest Georgia.

This dynamic project roves to different neighborhoods in our community in order to capture the perspectives of as many people as possible. I hope you will feel compelled to attend the March 18 workshop and contribute to the patchwork project. The workshop will focus on envisioning the future growth of our town; this vision will be shared and painted on a canvas square, then sewn together with other squares and displayed publicly in April.

DETAILS

In collaboration with Thomasville History Center’s “Slides of March” lecture series, Thomasville Center of the Arts presents a workshop envisioning the future of our community and offering guests an opportunity to contribute to the patchwork project.

Bring your own picnic dinner and eat on the grounds before the workshop begins at 7pm.

FREE. Workshop 7pm – 8pm, March 18.