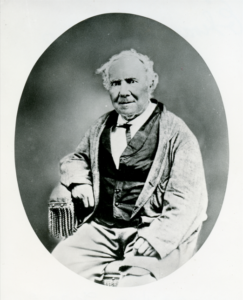

“Another Bad Day”: The Diary of Henrietta Eugenia Vickers Armstrong (Part 3)

What must it have been like to live in Thomasville at the brink of the Civil War? Here at the History Center we have the transcript of a diary written by a young, seventeen-year-old woman over the year of 1861. This diary not only gives us insight into this question but also paints a vivid picture of life in South Georgia and how it was about to drastically change. Follow along as we explore the world from Henrietta Armstrong’s point of view in this blog series!

_______________________________________________________________________________

When we last checked in on Henrietta, she had just learned that her brother was joining the Confederate Army. At the same time, she was home in Smithville nursing her sick husband and wondering what would come next. Her diary is heading into the summer of 1861 at this point. The weather is heating up, the crops are drying out, and tensions are rising alongside the thermometer. Let’s see what happens with Henrietta next.

Within the first few days of June, Henrietta is already having a very relatable Southern summer. Just as we are accustomed to here, the weather was hot and they were in desperate need of rain. As Henrietta most appropriately put it, “My garden is literally burning up” (June 11, 1861), showing that even over a hundred fifty years ago, teenagers were throwing the word “literally” into any sentence.

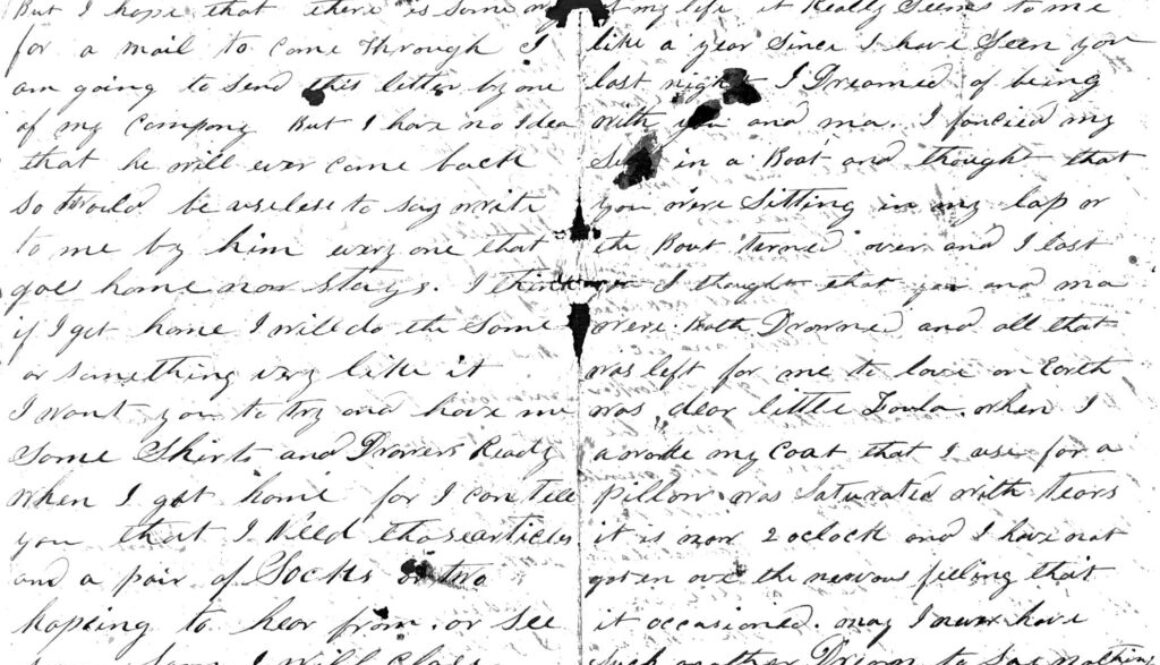

In the meantime, Aeneas continued to struggle with his health. Despite beginning the month on a good note, within two days he was back to ailing, this time with “weakness of the stomach.” Coincidentally, he had just started taking a new medicine prescribed by a Dr. Mettaver a few days before. But the pendulum would soon swing back in Aeneas’s favor as Henrietta reported,

“Aeneas is a great deal better today. He applied, last night, a mustard plaster to his stomach and it has relieved him almost entirely of the soreness in his stomach.” (Tuesday June 3, 1861).

Science Museum Group Collection

Mustard plasters were a popular remedy for aches and pains and were made by grinding up mustard seeds, mixing the powder with flour, and applying the mix under a bandage to the affected area much like the 1800s equivalent of an Icy-Hot Patch. The powdered mustard warms the skin and muscles – although leaving it on for too long could lead to burns. Whatever was ailing Aeneas this time, the patch seemed to help with the pain. But as seems typical for the Armstrong family, Aeneas’s good health only lasted a month until he spread a cold throughout the entire plantation.

Henrietta’s journaling from this time reveals her feelings about Smithville and life in the country in general during this time: it was dull. She states,

“We are lonesome. We see nobody at all and hear nothing.” (Friday, June 7, 1861).

The closest the Armstrong’s came to social interaction was through letters back home (including one that contained a picture of Buddie’s daughter, soon to be named Henrietta after her aunt) and conversing with the hired and enslaved workers on the plantation. The hired workers were Mr. Price, the plantation overseer, and his wife, both of whom seemed to be frequently in trouble for borrowing or taking more than they should of the Armstrong family’s food and resources.

With none of their family or friends around for dozens of miles and very little in town to do, their entertainment came from reading books (most of which they’d already read), playing the piano (which Henrietta forgot how to do), and trying out foods from the newfangled technology of cans and tins. From this we get thrilling updates like:

“Aeneas opened a can of fresh salmon this evening. He enjoyed it very much.” (Thursday, June 6, 1861).

The next day they tried canned corn and tomatoes which were “very nice indeed.” Complaining about their situation, Henrietta admits,

“This life is getting to be very wearisome and monotonous. Aeneas is improving though everyday and I hope that he will continue to exercise prudence and take good care of himself. He is still reading “The Last of the Barons.” I have nothing to read myself. I have read every thing in the house and I am, to use a French word ‘ennuyed’ almost to death. I wish I could get my [sewing] machine, I could then do some work. As it is I have nothing to do. Aeneas and I played cards awhile this evening and then he opened another can of salmon.” (Wednesday, June 12, 1861.)

But things were about to get going. Within a few days the couple ventured out to town to retrieve Henrietta’s sewing machine that was brought by train from Macon. After learning about the intensifying fighting in Virginia between the Union and Confederate troops, Henrietta felt invigorated to help the Confederate troops.

“We were victorious in every encounter. It looks as if Providence is on our side. Mrs. McAfee gave me some drawers to make for the soldiers, I have my machine now and can get along very well.” (Saturday, June 15, 1861).

On top of her work for the soldiers, she made several new clothes for the enslaved workers on the plantation including “three shirts for Edmond, Evans, and Wilson and two dresses for Adeline and Chloe” followed by “three pairs of britches, and one dress for Malinda,” and slip dresses for the children. To make matters more exciting, Henrietta spotted a comet passing by for several days in July, remarking,

“I was very much astonished tonight by seeing a large comet in the West.” (Tuesday, July 2, 1861)

She went on to mention the comet over several days, with it only seeming to disappear from view by the middle of the month. This turns out to be “The Great Comet of 1861” which was first seen in Australia over a month before Henrietta could see it. Several notable people across North America also wrote about seeing the comet. And if you can wait around until 2267, you could see it too!

By the end of July, Henrietta remains fairly bored with the occasional bit of news keeping her spirits from sinking too low.

“Next Wednesday is my birthday, I will be eighteen years old. I feel ten years older at least… I wish some of our relatives would visit us.” (Friday, July 26, 2861).

Unfortunately, Henrietta would have to wait another few weeks to see her family and friends. In the meantime, she lost some friends following the death of two Macon men during a battle in Virginia and the elopement of a young woman from a neighboring home who ran away with the Armstrong’s previous overseer.

Despite her ongoing boredom in Smithville, things were heating up across the country and the consequences of the Civil War were soon to come home to the Armstrong family. Will Buddie and Aeneas be called up? Will Henrietta get to leave Smithville? Will canned salmon be on the menu again? Join us next time to hear how life is about to get more interesting for Henrietta and Aeneas.