What’s Love Got to Do with It?

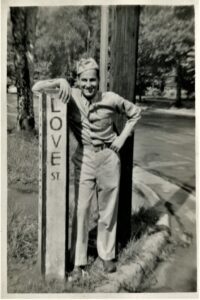

Love is in the air and on the shelves this time of year, making it a good time to talk about love in Thomasville. Not the gushy community love or loving our neighbors, but love with a capital L. The Love that can be found on Love Street in the Tockwotten Neighborhood. How did this street get its name? Was it Victorian sentimentality? Or is there more to the story? Let’s find out!

Look at a map of Thomasville and you will see that Love Street runs for about four blocks in town, from Washington Street to Remington Avenue. It’s a residential street lined with dozens of vernacular Victorian houses of all different shapes, colors, and sizes. But what’s Love got to do with it? To answer that question, we have to get to know the neighborhood.

In the History Center’s map collection, we have a series of maps put together by the late Judge Roy M. Lilly Jr. who researched the various city limits of Thomasville over the last 200 years. In 1857, the city limits expanded to cover the area we now know as Love Street. This was huge growth for Thomasville as the former city limits had not included this area nor a nearby town known as Fletcherville. So why were they adding this land to the city limits? The area only covers a neighborhood today, so why was it not part of the original limits? We have a clue to this question hiding in our maps.

Lebb Dekle, a well-to-do merchant, politician, and overall man-about-town, made his own map of Thomasville in this time period. It barely covers the area that would become Love Street. In fact, that space on his map is demarcated with a giant blue trapezoid. But if you look very closely you can see that the space reads “Tan Yard.” Tanning yards were work spaces for tanners or people who turn animal hides into leather. It’s a smelly business as you might imagine so tanning yards were often on the outskirts of town – just close enough for the workers to walk there from home and into town but not close enough to make people complain about the smell. From this we can gather that the tanning yard was on the move around 1857, opening up the land for citizens to build a residential community.

But where does the name “Love” come into this tanning yard-turned neighborhood? For that answer, we need to look into the homes dotting the street. Take a walk down Love Street and you’ll notice those Victorian houses mentioned previously. One of those houses bears a wooden plaque marking it as the P. E. Love House. But who was P. E. Love, and what did he do to have a street named after him?

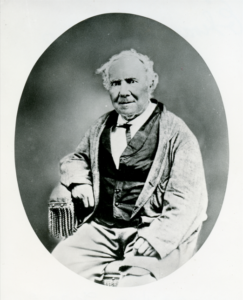

Peter Early Love was born in 1818 in the town of Dublin, Georgia, about three hours northeast of Thomasville. His parents died when he was still a young boy so his older sister and her husband raised him. When Peter was old enough, he attended Franklin College, now known as the University of Georgia. After graduating, he traveled north to study medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, which was the place for Southern students to learn medicine at the time. He quickly realized his heart was not in medicine and decided to take up law instead.

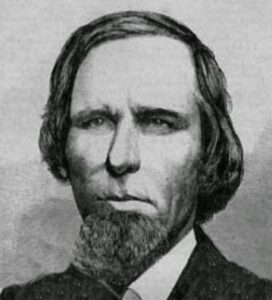

In 1839, Peter returned to middle Georgia and began his study of law alongside several future Thomasville lawyers. Peter and the young lawyers descended upon the still fairly new town of Thomasville and set up shop. As Peter rose through the ranks, he became a delegate in the electoral college during the presidential election of 1840. His vote helped elect William Henry Harrison as the nation’s 9th president (before he died of pneumonia one month into his term). A few years later, Peter was made Solicitor General of the Southern Circuit, meaning he rode all over Southwest Georgia trying cases for the State. This also meant he spent a lot of time away from home – but that didn’t stop him from putting down roots in Thomasville.

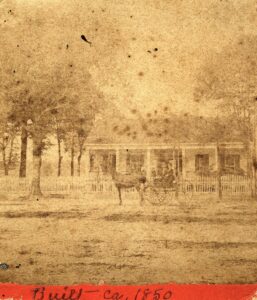

Back on the farm, Peter was setting up a home with his wife and four children. He bought a large tract of land in what is now known as the Love-Tockwotten neighborhood. Peter began dividing up the land soon after and selling it to his many friends including the Hansell family and the Remington family. He kept just enough land for himself and built a simple wood-frame dwelling around the year 1850. He called his house “Love Mansion.” Work on the house finished just in time for Peter to leave Thomasville to act as a Georgia Senator in Milledgeville.

After his term as a senator, Peter was made Judge of the Southern Circuit, replacing his friend Augustin H. Hansell. On top of that, Peter started his own local newspaper: The Wiregrass Reporter ran for several years before the start of the Civil War. He was also made captain of the Thomasville Guards, a local militia group, and helped lead the formation of Young’s Female College in town. When he grew restless for the next big adventure, Peter became a member of the United States House of Representatives.

This was a short-lived trip. Peter was elected just as the Civil War was breaking out. He was pro-secession, so when Georgia and many other states left the Union, Peter and his fellow Southern congressmen packed up their bags as well. He returned home to Thomasville, but not quietly.

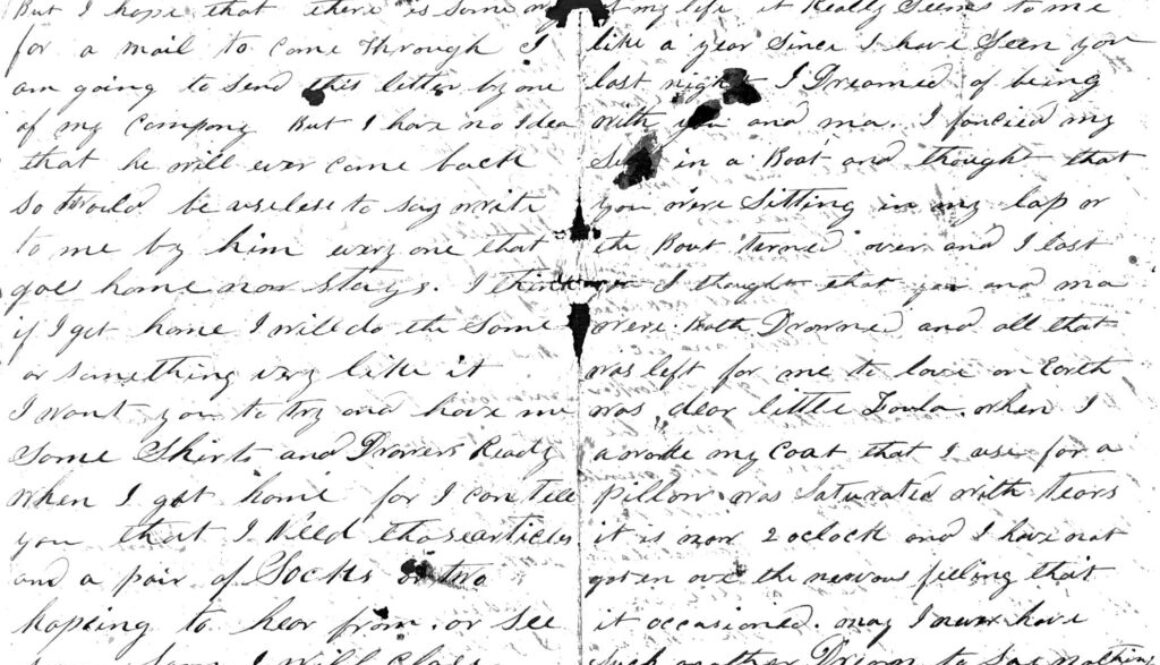

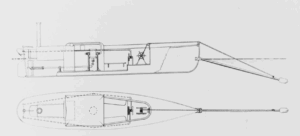

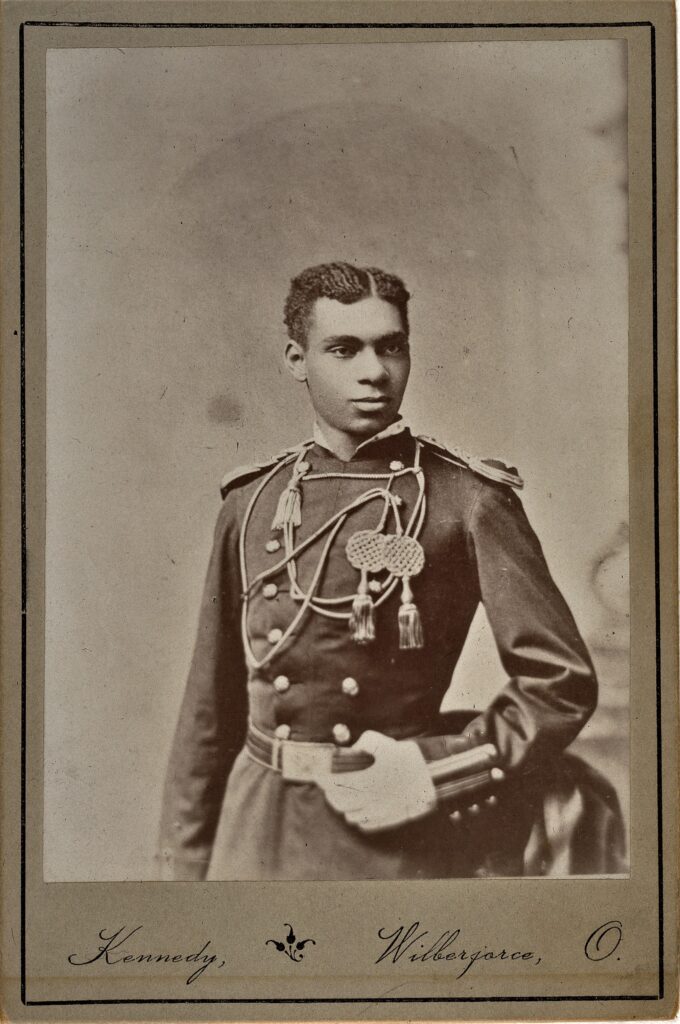

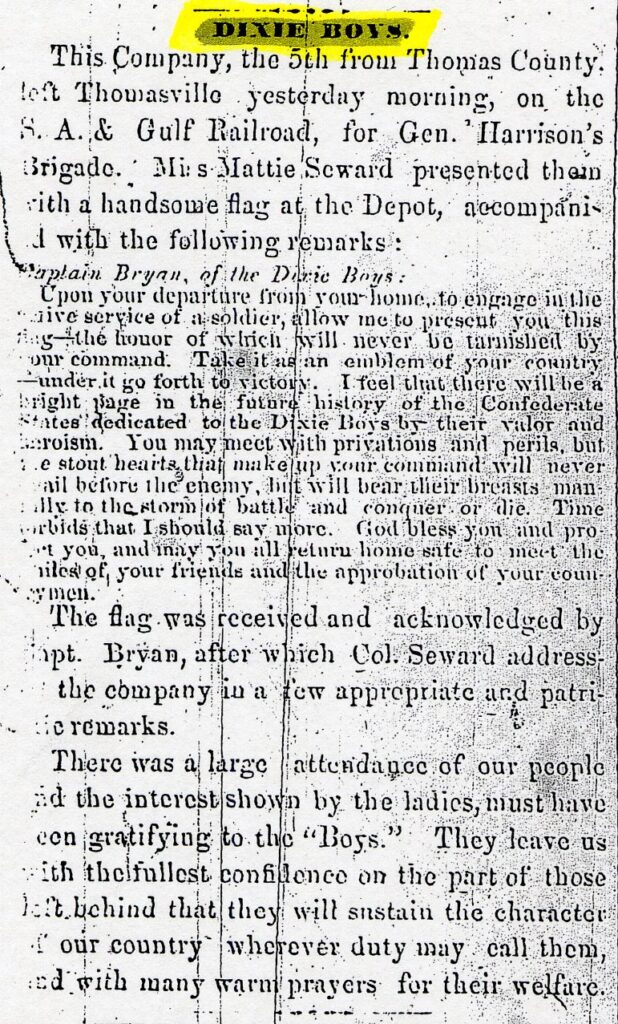

Peter returned to his post as captain of the Thomasville Guards. In the years before the War, the Guards mainly spent time doing drills and participating in parades and social events. Despite being a militia, the Guards were more of a social club for the young men of Thomasville. Even Peter admitted the “Light Infantry is a company of boys, as brave, as enthusiastic as any, but still most of them are boys… They would ostracize me if they only knew that I had doubted for a moment their perfect equality with all other companies…” Despite his feelings, the Guards were sent to fight in the Civil War – this time, without Peter as their captain.

Peter stayed behind to serve in the Georgia State Legislature, now one of eleven states making up the Confederate States of America. Not long after, he was made mayor of Thomasville.

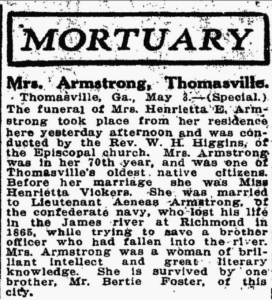

The end of the Civil War brought Union troops to Thomasville as part of President Andrew Johnson’s plans for Reconstruction. Ever true to his personal beliefs and staunch support of secession, Peter resigned from his post as mayor. Having burned the candle at both ends all his life, Peter died on November 8, 1866 at the age of 48. He was buried in his family’s plot at the City Cemetery, only a few blocks away from the courthouse he spent so much time in.

As for the street, it earned its official name around the 1870s. The earliest mention of the street by that name shows up in a newspaper article from 1875. That was one of the first years the town of Thomasville held Independence Day celebrations following the Civil War. The Thomasville Guards marched from Broad Street down to the Love Mansion on Love Street where attendees gave speeches and read the Declaration of Independence, a fitting tribute to the man who gave his name for this street.