Skirting the Issue: Our Connection to Lafayette

Over the next ten years, our country will be headed into a monumental celebration as we mark 250 years since the signing of the Declaration of Independence and our start as a new nation. One of the major players of the American Revolution was an unlikely supporter: the Marquis de Lafayette was born into the French nobility and was only in his twenties when the War began. Despite his unlikely beginnings, he rose up to become one of the greatest leaders of the Revolution and remained popular among Americans for the rest of his life. His popularity allowed him to travel the country during many celebratory tours, with his Farewell Tour taking place in 1825. As people across the country commemorate the 200th anniversary of this trip, let’s check out Thomas County’s own connection to the military leader and “Guest of the Nation.”

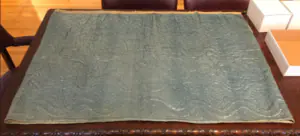

The History Center has a skirt in its collection that dates to the late 18th century. It is composed of an outer layer of blue silk and an inner layer of plain linen that have been quilted together. There is no shape to the skirt. Instead, it is made up of six rectangular panels sewn together with a set of drawstrings on each “side” end of the item which can be pulled in to give the skirt a shape. The only clues we had for this skirt came from two little labels inside: one piece of cloth tape that had “BIBB” written in ink across it and a little piece of paper pinned to the lining that read, “This skirt was worn to a ball given in honor of General Lafayette, with this skirt was born a court train of brocade satin with pink roses.” So where did this skirt come from? And was it really worn to a party for the Marquis? We had to find out!

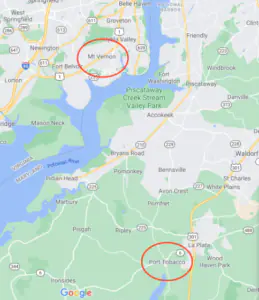

Our records revealed the skirt was given to the History Center by a lady named Gladys Bibbs in 1989. Her story was that the skirt had been passed down through her family for generations, a family by the last name of Adams. Naturally we checked out her line on our ancestry.com account: it turns out she was related to a family named Adams who lived in Maryland along the Potomac River. So here we have a colonial-era family living in a prominent area and owning this skirt – but does that mean it went to a party for the Marquis?

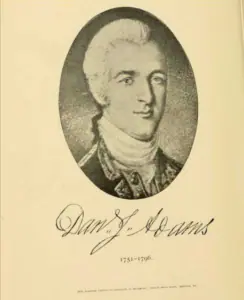

We looked into Gladys’s ancestors: Nancy Ann Hanson (b. 1761) who married Daniel Jenifer Adams (1749-1796). While Nancy was our skirt wearer, we were curious about her husband too. Daniel was named after his maternal uncle, Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer, a prominent plantation owner, politician, and signer of the Constitution of the United States. On top of all that, this uncle was best friends with his neighbor who lived across the Potomac – George Washington.

Thanks to his uncle, Daniel Jenifer Adams had access to the big man himself. Washington kept meticulous notes of his days in his journals, listing who came to supper and who stopped by on business. He also kept many of his letters and records related to his business. It’s in these records we see that Washington and Daniel were very much involved in each other’s lives, but Washington may not have been too happy about that!

In one letter, Washington called Daniel “the most worthless young man.” There were several times that Daniel let the General down. The first time came when Washington let Daniel sell some of his produce. They agreed Daniel would sail down to Bermuda, sell the grain, and use the money to buy items on Washington’s grocery list. Daniel sold most of the grain in Bermuda. But then he took a little detour to Jamaica and bought the ship he had been sailing on, including all the goods on board. With the way the deal with the ship owner was set up, this sale of goods meant Washington would not get his money back for his grain still on the ship. As you might imagine, Washington was a little upset about this! He sued Daniel, forcing the young man to sail back to Virginia where Washington put the boat up for auction trying to make back his lost money. Unfortunately, no one wanted to buy the boat, and Washington ended up having to buy the boat from himself for $300.

Another issue came up during the American Revolution. Daniel joined the Maryland Militia Line, a group of volunteer soldiers in charge of protecting the colony against the British and serving under the direction of General Washington. Daniel did surprisingly well in the military; in fact, he was the fourth best Major in the Maryland Militia. Until his pride got in the way.

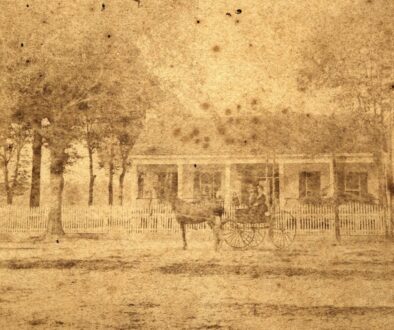

By the end of 1779, Daniel had been passed over for promotion, and worst of all, it went to someone he despised. Daniel wrote a letter to Washington explaining that while he knew this was crunch time for the Colonial Army, being an army major didn’t pay enough for him to support his new family (he had just married Nancy). This wasn’t a total lie: Daniel’s father had just died with several debts to be paid. Washington stepped up and offered to buy the Adams family home and pay off their debts – a fairly grand gesture! Daniel agreed to the arrangement but kept coming up with excuses as to why he and his sisters could not leave the home and why they were selling off pieces of the property that should have gone to Washington. Daniel was definitely down at this time, but with his wealthy and prominent uncle around, he was never out.

Years later, Washington became President of the newly formed United States. After the Revolution, Congress passed a bill stating soldiers who fought in the recent war would receive a pension for their service – but there was a catch. Only those who served from 1780 onward (a month after Daniel quit) were eligible. Daniel wrote a letter to his famous neighbor begging for help with Congress. He told Washington his prior military service had left him in poor health and his attempts at work had been less than successful. Washington never replied.

Don’t feel too bad for the Adams family. When Uncle Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer died in 1790, he left his 16,000-acre plantation to Daniel – so life couldn’t have been too bad for him, right?

So now we’ve found the connection between the Adams family and George Washington, but how does that put our skirt in the same room as Lafayette? During the War, Washington and Lafayette formed a father-and-son bond that would last the rest of their lives. When the War ended in 1784, Lafayette was hailed as a hero in America and began touring his second homeland on a celebration tour.

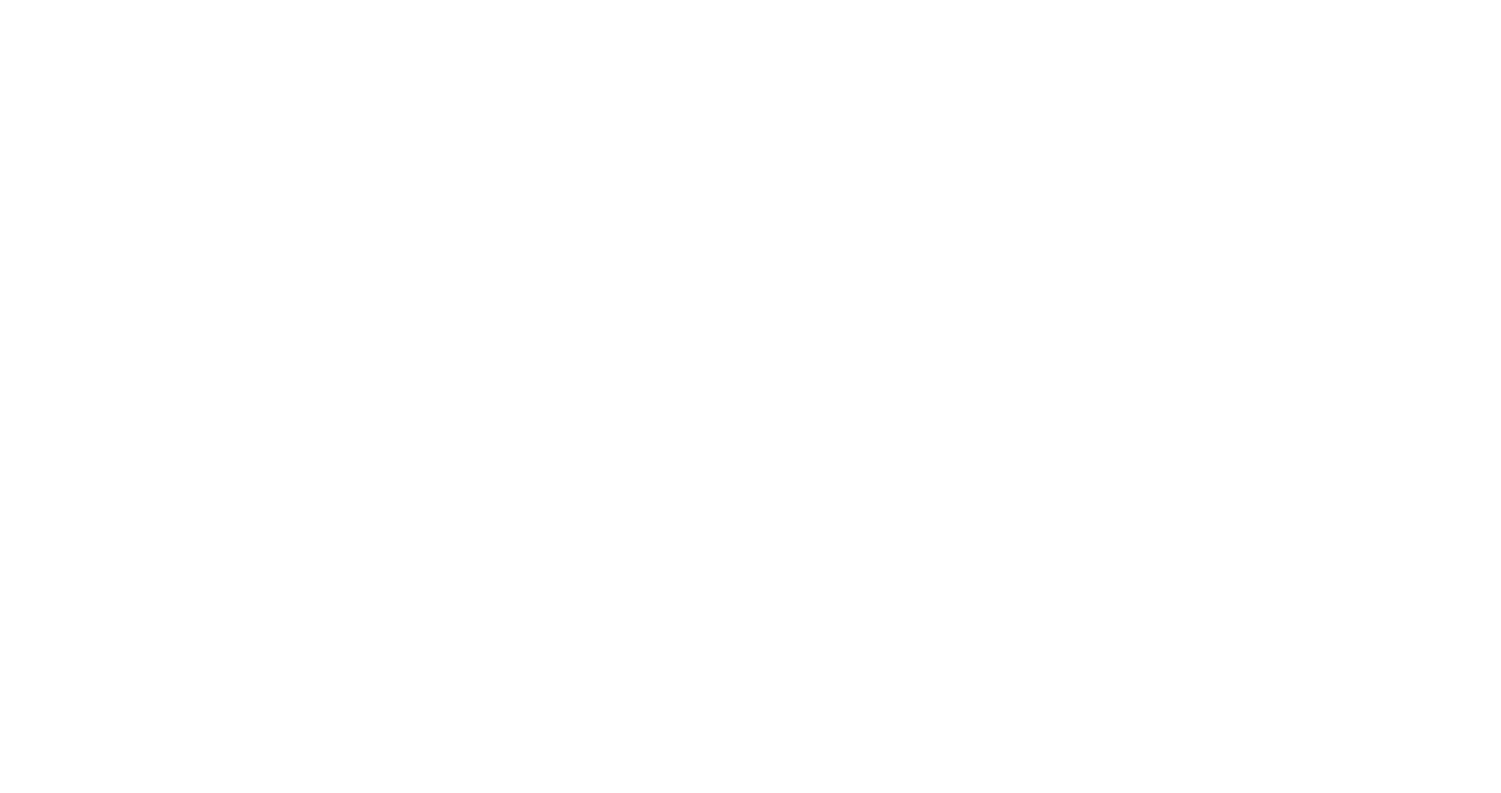

One of his first stops was in August of 1784 at Mount Vernon, Washington’s home along the Potomac. Washington and Lafayette partied for ten days before the Marquis continued his tour. On the invite list to this ten-day festival were many of Washington’s friends and neighbors. We can surmise that Daniel and Nancy Adams were guests at one of these parties where Nancy might have worn the skirt that now resides in our collection. The timing works out as Nancy would have had about a year to recover from the birth of her second child in 1783 and wouldn’t be pregnant again for another two years.

So if you’re feeling down, just think about this beautiful skirt and remember that no matter what, at least George Washington never called you “a worthless young fellow.”