Problems with Peter: The Peter Dekle Letters

Here at the History Center, we like to supply our collections department interns and volunteers with interesting projects that illustrate what life in Thomas County’s past was like for her citizens. We have many letters, records, diaries, and documents that give sneak peeks into the daily lives of people who were more like us than we may realize.

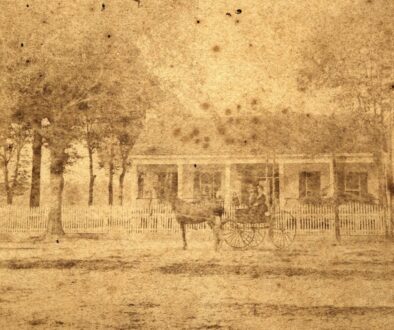

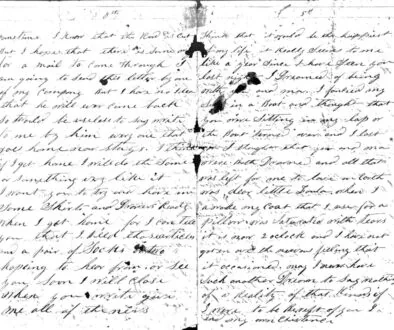

One of our interns, Kayla Reeves (who recently attained her bachelor’s degree in history from Florida State University), was tasked with transcribing a collection of letters from Private Peter Dekle (1836-1863) to his wife Susan Dunbar Dekle (1839-?) of Thomasville. Peter’s letters span from April of 1862 to August of 1863 when he served in the Confederate Army in Company F of the 29th Infantry. For most of his military service, Peter was stationed around Savannah but was later sent to North Carolina and Mississippi before he was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga. After several months, he succumbed to his injuries; however, the whereabouts of Susan following her husband’s death are currently unknown.

Here’s what Kayla had to say about Peter and his letters to Susan:

“As a drafted soldier, Peter did not generally discuss ideological reasons behind the war in his letters, rarely mentioning secession or even regional animosity. However, Peter’s letters provide valuable insight into the experiences and mentality of an average soldier, demonstrating themes of homesickness, despair, adventure, and adjusting to the general monotony of camp life.”

In this blog series, Kayla explores some of these themes with excerpts from Peter’s letters. Please keep in mind that Peter was writing in the language and attitudes of his time which we now consider to be racist and prejudice.

Hardships of Camp Life

A large portion of Peter’s letters discuss his frustrations with the war and the hardships and monotony of camp life. From dealing with the daily grind to fighting the environment, there were many reasons for a soldier to feel despondent. For example, in one letter from July 25, 1862, Peter states,

“hate to see morning cum time. I rise in the morning the very same old thing over untill we go to bed, if I could only get ten or twelve days ever[y] three or four months it would not go so hard with me,” [1980.04.06].

Camp life was a 24/7 job with few opportunities to leave for home. Despite a seemingly grueling schedule, much of the day was spent waiting: waiting for drills, waiting for food, waiting for the next orders, waiting for the end of the day. The monotony was enough to make Peter desperate for time at home as evidenced further in the letter when he wrote,

I think they will send us off sum where before long up in the northern sates [states]. if they do I no [know] I will not go home as long as I stay in service unless[s] I were to get sum [some] of my limbs shot of [off]. then probily I may get of [off] to go home,” [1980.04.06].

While this statement may seem a bit dramatic, the probability of being seriously wounded or worse in battle was always high and a constant threat in the minds of soldiers. Fear of losing a limb or life in battle coupled with the long and boring days of camp life would make anyone yearn for the safety of home.

Adding insult to injury, Peter also had to deal with his new environment. While his encampment in Savannah was not too foreign of a location for this South Georgia man, he still suffered from being outside during the summer. On August 21, 1862, Peter wrote,

“when I am of [off] on duty four or five miles picketing, seting [sitting] on my post [?] the late hours of knight [night] and the sand flies and the mosquitoes are as thick as you ever saw bus [buzz] around the gum and raining as hard as you ever saw it and daring not to leave your post and half starved out at times,” [1980.04.06].

We can all relate to the misery of being swarmed by mosquitoes. On top of that, Peter did not have enough food as rations for Confederate soldiers were meager throughout the War.

All these factors made camp life miserable for Peter. He frequently wrote about his homesickness and his desire to see his wife and child, stating,

“I am in hop [hope] this reched [wretched] war cant last much longer but I am affraid it will last longer than I will. I have given out the idia of ever gettin of [off] as long as the war lastes but that do not hender us for not wanting to go home. you cannot experance [experience] my feelings when I think of you and home. no one could not have such feelings unless they were bound down like we are, nothing we see or here [hear] are no satisfaction to us. no injoyment [enjoyment] in camps. one thing over ever[y] day til I am perfectly disgusted,” [1980.04.06].

Peter describes the mentality of the soldiers in the camps, similarly to his own, stating,

“you cant imagine how a pore soldier wants to see home. home are the cry among them all the are [there are] nun [none] of us ever new [knew] what a good home wher [were] until we had to leave it. I thought we lived heard [hard] but we lived like fatning [fattening] hogs. I would rather be at home without any thing at all than to be here with thousands. I can think about the pleasure we have had together and I am far of [off] from you and cant help my self. it goes very heard [hard] with me, hearder [harder] than you can imagine, thought I will have to stand it the best I can whether I like it or not” [1980.04.12]

Peter seems remorseful for realizing too late how good his life at home had been. Like other volunteer soldiers, the thrill and adventure of war seem to have worn off and uncovered a grim and monotonous reality for Peter. In the end, he could only try to bare his situation out until the end.