Open Position: Executive Director

JOB SUMMARY

The Thomasville History Center (THC) in Thomasville, Georgia, is seeking an experienced museum professional who will serve as the Executive Director to oversee this medium-sized organization with a $500,000 annual operating budget and four full-time staff. The Executive Director, in partnership with a responsive and experienced board, will be responsible for all aspects of the institution and will oversee everything from day-to-day operations to comprehensive long-range planning. The ideal candidate will be an innovative, experienced museum professional who is a collaborative leader, an articulate communicator, and a proven development professional. This position will report directly to the Board of Directors.

In existence since 1952, the Thomasville History Center is in Southwest Georgia in the heart of the Red Hills Region, an area known for its rich history, rolling hills, and red clay soils. Thomasville is a thriving, vibrant community of multi-generational families and civic-minded people. The community repeatedly appears on lists of the best places to live, work, and visit. The Thomasville History Center’s four-plus acres of land encompass two campuses, including thirteen historic structures and a collection of over 500,000 items covering the history of the region.

The Thomasville History Center enjoys tremendous community support. The THC maintains extensive regional partnerships that exist to meet its mission to “connect the Red Hills’ past with its present to inspire and enrich current and future generations.”

The Executive Director of the THC will lead the organization through the implementation of a recently completed Strategic Plan through which the THC will play a larger and more prominent role in the community and the Red Hills region. In addition, the organization’s resources hold enormous potential for the future as the THC’s Board, staff, funders, volunteers, and partners will provide the ED with countless ways to move the institution forward.

PRIMARY DUTIES:

Development

The ED is the primary fundraiser and is responsible for all development-related work such as cultivating donor relationships, securing and administering grants, building new financial partnerships, and managing the Fund Development Committee.

Marketing

The ED is responsible for overseeing marketing efforts and promoting THC’s brand and public awareness in the community and the Red Hills region. Community engagement and educational opportunities that attract a broad range of audiences are key to these marketing efforts.

Fiscal Management

The ED is responsible for drafting and managing the annual budget and has primary responsibility for managing all fiscal needs including managing investments, tax reporting, and organizational regulatory responsibilities.

Board Relations

The ED works closely with the THC’s 11-member board to create the vision and set the direction of the THC. The ED chairs the Board Development Committee and manages board communications, meetings, and development.

Strategic Planning

The ED oversees and manages all planning-related needs. This includes working together with the staff and Board to meet and exceed the goals of the current strategic plan as well as updating strategic initiatives in the future.

Human Resources

The ED is responsible for managing and directing the THC’s staff, ensuring professionalism, communication, and teamwork across the organization.

DESIRED QUALIFICATIONS

- A heart to serve, committed to the mission of the THC through service to the organization and the community.

- Senior-level management experience in a fast-paced, small to medium-sized non-profit organization with an M.A. in history, public history, museum studies, or education from an accredited college or university and familiarity with museum professional standards in areas such as collections, interpretation, administration, and education.

- Demonstrated ability to engage a variety of audiences in ways that generate excitement and promote the well-being of the THC

- Track record of successful collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders across the Red Hills Region to generate both earned income and long-standing funding support.

- Cultural sensitivity and diplomacy, emotional intelligence, and commitment to the highest standards of professionalism

- Proven financial management with success in managing budgets and facilities

- Familiarity with social media platforms, email programs, customer management databases, basic accounting, and graphic design

- Applied knowledge of professional museum principles, practices, and procedures and current issues in the field of museum education, including knowledge of research tools and methodology

- Excellent communication (speaking, writing, presentation, and listening) skills and an ability to effectively communicate with all levels of the staff, as well as with external audiences such as vendors and contractors

- Demonstrated organizational planning, problem-solving, and collaboration

- Effective interpersonal skills, judgment, and discretion

- Excellent computer skills with proficiency in Quickbooks, Excel, CRM, and various database platforms such as Square and Past Perfect

WORKING CONDITIONS

- Work is predominately done in an office setting

- Must have the ability to complete certain physical activities.

- The position will require occasional work on weekends and evenings.

- There will be instances where the position will be working in outdoor environments in all types of weather.

- There will be instances where work will take place in crowded, cramped, or small work areas.

- Occasional exposure to cleaning agents or chemicals

Minimum travel will be required, less than 10 percent.

Applicants must submit a cover letter and resume to historycenterresume@gmail.com

The speaker at the conference was Karl Rove. I saw Rove step out into the cocktail party and told Margaret Ann (my wife) I was going to get a photo with him. I pushed my way through the line and informed Rove that I was a high school history teacher and would use the photo in my class. He obliged.

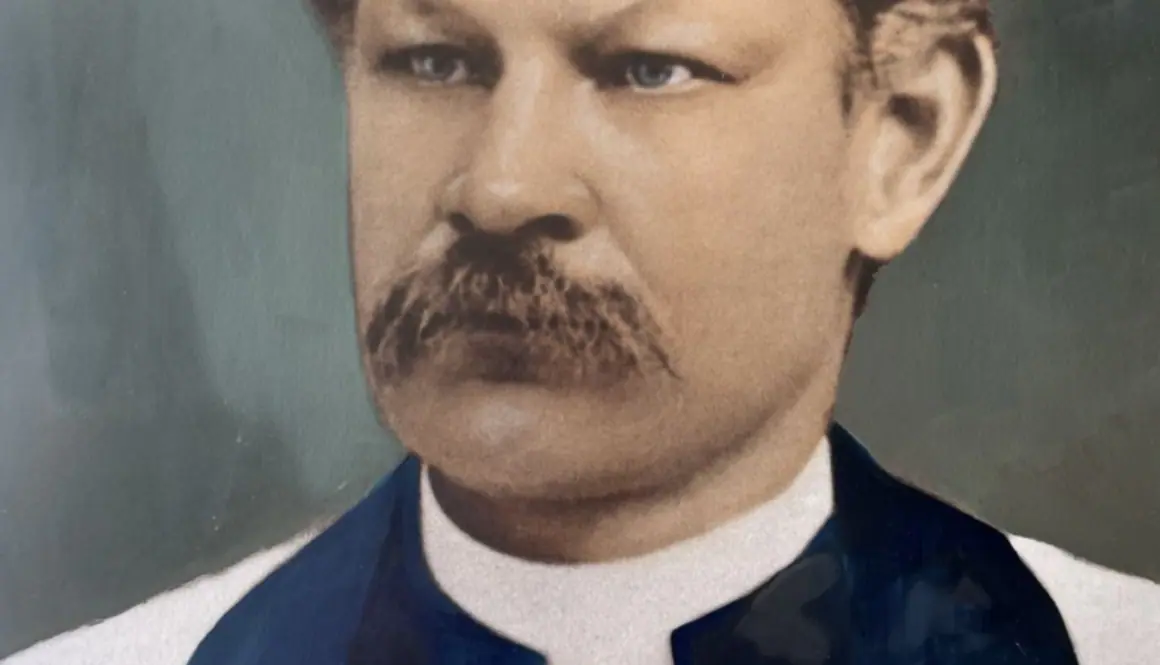

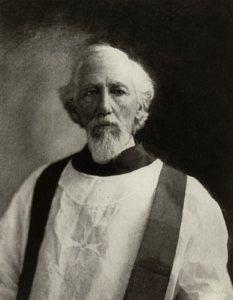

The speaker at the conference was Karl Rove. I saw Rove step out into the cocktail party and told Margaret Ann (my wife) I was going to get a photo with him. I pushed my way through the line and informed Rove that I was a high school history teacher and would use the photo in my class. He obliged.  leaders (former Union Soldiers) who gathered in Thomasville in 1896. Did LaRoche have a political agenda? Yes. It was helping communities and people flourish. It was political, spiritual, and theological. When LaRoche left St. Thomas, the Thomasville newspaper described him as having “endeared himself to all classes of people by his genial ways and blameless walk.”

leaders (former Union Soldiers) who gathered in Thomasville in 1896. Did LaRoche have a political agenda? Yes. It was helping communities and people flourish. It was political, spiritual, and theological. When LaRoche left St. Thomas, the Thomasville newspaper described him as having “endeared himself to all classes of people by his genial ways and blameless walk.”